Spirituality in Hollywood had been represented by religious-themed films as early as the silent years, and became a studio staple in the 1940s and 1950s. Religion depicted on screen in that era came through a succession of Biblical tales (e.g. SAMSON AND DELILAH, DAVID AND BATHSHEBA, THE ROBE), and with the advent of the wide-screen, culminated in the gargantuan commercial success of both Cecil B. Demille’s THE TEN COMMANDMENTS (1956) and William Wyler’s BEN-HUR, Oscar’s best picture of 1959. By the early 60s, the genre was reaching its final stages, and 1962 offered some prime examples of the “Bible epic.”

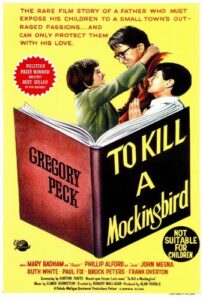

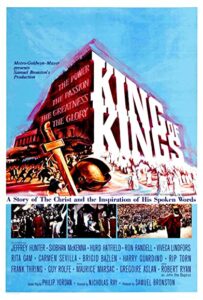

KING OF KINGS premiered in October of 1961 as a roadshow in select cities, and then went into general release in the Spring of 1962 in time for Easter season. Produced by European showman Samuel Bronston, and helmed by American director Nicholas Ray in temporary European exile, the film received mixed reviews at the time. Bosley Crowther of the New York Times did compliment “a certain photographic reverence and purely pictorial eloquence,” and praised Twentieth-Century-Fox contract player Jeffrey Hunter’s portrayal of Jesus Christ for “simplicity and taste.” Hunter had been a controversial choice for the Messiah; his youthful appearance, striking good looks and piercing blue eyes (which led Ray to cast him) incited some critics to derisively dub the film “I Was a Teenage Jesus,” even though he was the same age (33) as Christ.

Hunter co-starred in two other films later in 1962, NO MAN IS AN ISLAND, and the star-studded THE LONGEST DAY, but his career was tragically cut short by his accidental death in 1969. KING OF KINGS would be the peak of his career. The film has since been reevaluated as one of the strongest of the Bible epics, with Leonard Maltin extolling, “the life of Christ, intelligently told and beautifully filmed, full of deeply moving moments.”

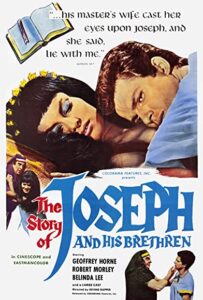

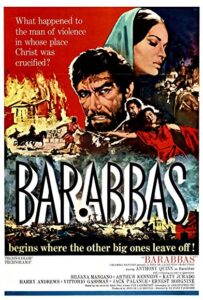

Other Bible movies on U.S. screens that year included the Italian hodgepodge THE STORY OF JOSEPH AND HIS BRETHERN, with American actor Geoffrey Horne in the title role. Horne made a promising screen debut in a key supporting role in THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI (1957), but his star faded quickly in a number of ill-chosen films. JOSEPH was prime fodder for the critics; The New York Times called it “the clumsiest, the silliest, the worst of the quasi-Bible story pictures to come along since the wide-screen era was born.” On the other hand, BARABBAS, an international opus starring Anthony Quinn about the thief who was exchanged for Christ for crucifixion, received the best reviews of the ’62 religious films, morphing from a gladiator story to a tale of spiritual redemption. The New Yorker’s Michael Sragow cites “Christopher Fry’s pointed and intelligent free adaptation of Pr Lagerviskt’s 1950 novel resists grandiloquence.”

Despite the box-office success of the majority of these films (JOSEPH, incidentally, was an unsurprising flop) the Bible epic era was coming to a close. SODOM AND GOMORRAH (filmed in 1962, released in 1963) had only modest box-office returns despite the well-worn formula of salacious sex, sanitized violence, and crafted action mixed in with religiosity. The critical and commercial failures of George Stevens’ THE GREATEST STORY EVER TOLD (1965), a particularly ponderous and over-reverential effort, and John Huston’s THE BIBLE (1966), a monumental misfire to which Maltin advised viewers to “definitely read the Bible instead,” put a coda on the genre.

After abandoning religious-themed films, the “New Hollywood” of the post-studio era rarely revisited Bible stories, and the relative failure of Martin Scorsese’s controversial THE LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST (1988) rendered the genre comatose once again. It was not until the 21st century that faith-based films could once again be found in the local multiplex or streaming on various viewing devices at home. But in 1962 audiences could see two of the best of the genre designed specifically for the big screen, BARABBAS and KING OF KINGS, at their local movie theaters.