CINESAVANT COLUMN

Hello! A Book Review today:

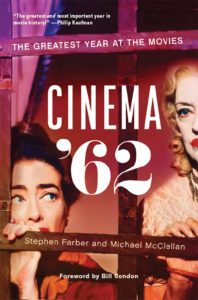

I just finished reading Stephen Farber and Michael McClellan’s film book Cinema ’62: The Greatest Year at the Movies. It’s a pleasing look at a special group of pictures through an unexpected filter. The premise challenges the standard notion that 1939 was the best year ever for American movies. At first glance that seems a strange idea, as we all have a personal ‘best year’ for films, usually from when we were young moviegoers, entranced by most everything we saw. I loved everything I saw from 1965 to about 1969, but I wouldn’t make a case for many of my favorites in those years to be the ‘best’ of anything.

Touting their magic year 1962, Farber & McClellan do much more than simply offer a list of candidates for the pantheon and fold their arms. They instead organize the output of ’62 as a gallery of trends and themes. In doing so they score good comments about the history of film from roughly the end of WW2, to the present day. Yes, expect plenty of arguments comparing the quality and range of ’62 to any decade that followed. Not even the Golden ‘seventies gets a pass, as that decade’s hits offered a narrowed subject range than ever — the film school generation didn’t make many films about women, for instance. John Frankenheimer released three movies in 1962, but the nature of the business today doesn’t allow a director to build that kind of career momentum.

The authors keep things honest by including pictures that opened for Academy consideration in ’61, but received their substantial release in ’62. The same goes for foreign films delayed in their U.S. release.

Most of the top pix of that year — Lawrence of Arabia, The Manchurian Candidate, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance — need little defense, but the authors push further to sell the idea that ’62 was a crossroads of top cinema culture. New talent were doing their best work (Ride the High Country) and independent film found its first big success (David and Lisa).

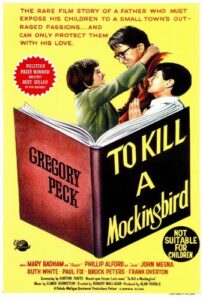

Actually, Farber & McClellan don’t need to do too much arm-twisting. They make a compelling case by showing how ’62 became a convergence point in a changing Hollywood. The Old Guard of directors bows out as new blood arrives, mostly from ‘fifties TV. A few classic-era actresses survive by reinventing themselves. And filmmakers in both Hollywood and the U.K. take on subject matter that was formerly considered taboo. Hollywood’s flirtation with psychology pays off with more mature pictures, and socially conscious filmmaking unites directors as different as Robert Mulligan (To Kill a Mockingbird) and Roger Corman (The Intruder).

We’re reminded that in ’62 B&W was still the norm for serious drama, as noted in Advise and Consent, Billy Budd, and The Miracle Worker. The text repeatedly underscores the uphill battle faced by actresses, the best of whom were considered uncommercial at forty while male stars older than 55 were cast in romances opposite women who could be their daughters. The book finishes with a full treatise on the making of Lawrence of Arabia. This account of the epic 65mm production begins by noting that producer Sam Spiegel began as a criminal illegal immigrant. 25 years later, Spiegel is accepting an Oscar and thanks the creatives who made the film — even though he refused to pay their airfare to the awards ceremony.

Serious film books are far and few between now, probably because there are fewer starry-eyed film majors who actually care about film history. I’m partial to the ‘film & politics’ historical narratives offered by J. Hoberman, and Cinema ’62: The Greatest Year at the Movies uses some of the same “look at the context, will ya” approach when deciding what is and isn’t relevant. Farber & McClellan also do a round-up of awards given out by various reviewing groups, a memoriam for venerated repertory film theaters that no longer exist, and a hefty list of 1962 also-rans. Those ‘losers’ naturally include a dozen genre favorites that this writer reveres more than many of the acknowledged winners in constant rotation on TCM.

This is a solid work of film study and appreciation that makes its case for a new ‘Golden Year’ quite well.

Thanks for reading! — Glenn Erickson