While the term “widescreen spectacle” could easily apply to the superhero and sci-fi fantasy franchises of the 21st century, which are routinely marketed as cinematic “events,” it came into use during the 1950s with the creation of formats that expanded the physical dimensions of the movie screen. These technological achievements, notably Cinerama and Cinemascope among others, were also amplified by the introduction of stereophonic sound. This is Cinerama premiered in September 1952, followed one year later by The Robe, in September 1953, the first film released in more accessible Cinemascope, launching the widescreen era. Although these technical and artistic breakthroughs advanced the art of film, they also served a useful economic purpose —to lure audiences back into movie theaters after television had vastly reduced theater attendance and threatened the survival of cinemas themselves, as many theaters had been forced to close permanently by this time.

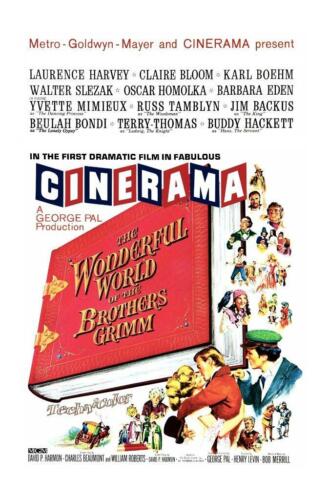

One exhibition method designed to restore regular moviegoing was the roadshow, an exclusive engagement of an extended-length movie (in some cases three hours plus intermission). These special features included limited daily showings, reserved seats, higher ticket prices and souvenir programs, shown in grand movie palaces in major metropolitan locations, primarily in the then viable downtown areas. Produced and distributed by the major Hollywood studios, which brought their marketing and publicity muscle, these films were the movie “events” of the period. By 1962, the widescreen era was still going strong, and saw the release of four major motion pictures in roadshow presentations: The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (in Cinerama), The Longest Day, Mutiny on the Bounty, and Lawrence of Arabia. How the West Was Won, the first filmed narrative Cinerama production, opened in Europe in the fall of 1962, but the U.S. release was held until February 1963.

The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm, the first narrative Cinerama release (and second produced) after a decade of travelogues and documentaries, opened in August and was aimed directly at the family trade. Commercially popular, it played until the end of the year, delaying the domestic release of How the West Was Won (since it occupied most of the existing Cinerama screens in the nation). It is also a prime example of what passed for fantasy filmmaking in that era, with painstaking, pre-CGI special effects by a team of craftsmen under the supervision of producer-director George Pal, particularly the Puppetoon animated segments first introduced by Pal in the 1930s, which are the movie’s highlights.

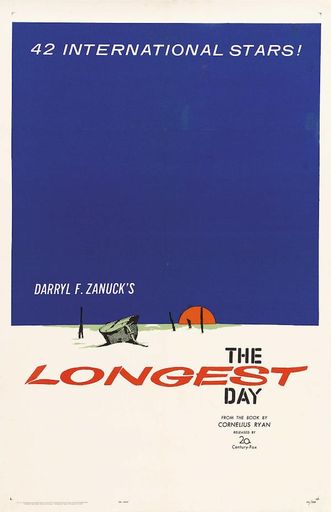

The Longest Day, a monumental film recreation of D-Day in WWII, opened in October to strong reviews and the lure of 42 international stars, ranging from major Hollywood luminaries John Wayne, Henry Fonda, and Robert Mitchum to relative newcomers Sean Connery and Richard Beymer (following his breakthrough co-starring turn in West Side Story). Filmed on location in Europe by studio titan Darryl F. Zanuck during his five year stint as an independent producer, who supervised three directors (and allegedly directed interior scenes himself).

The Longest Day, a monumental film recreation of D-Day in WWII, opened in October to strong reviews and the lure of 42 international stars, ranging from major Hollywood luminaries John Wayne, Henry Fonda, and Robert Mitchum to relative newcomers Sean Connery and Richard Beymer (following his breakthrough co-starring turn in West Side Story). Filmed on location in Europe by studio titan Darryl F. Zanuck during his five year stint as an independent producer, who supervised three directors (and allegedly directed interior scenes himself).

The film’s gargantuan box-office success as a roadshow demonstrated the commercial viability of the format, becoming the highest grossing movie of the year. Additionally, it proved equally successful with film critics, as it was listed in most year-end top ten lists and was named the year’s best movie by the venerable National Board of Review. Aside from the mammoth technical recreations of the D-Day invasion in a pre-CGI era, the movie is notable for its black-and-white cinematography (by three international craftsmen), which was counter to the era’s custom of filming widescreen spectaculars in Technicolor. Zanuck had decided he wanted a documentary look and approach, and monochrome was authentic to the vast majority of WWII films. In retrospect, The Longest Day was the ultimate WWII movie, appealing directly to the Greatest Generation, who successfully fought both the war and the specific turning point of D-Day, so faithfully recreated by the accepted filmmaking standards, techniques, and tropes utilized in 1962. In 1998 Steven Spielberg mounted a new take on the subject with Saving Private Ryan, a more violent and shockingly realistic depiction of the savagery of war, but his film is for the most part a fictionalized account.

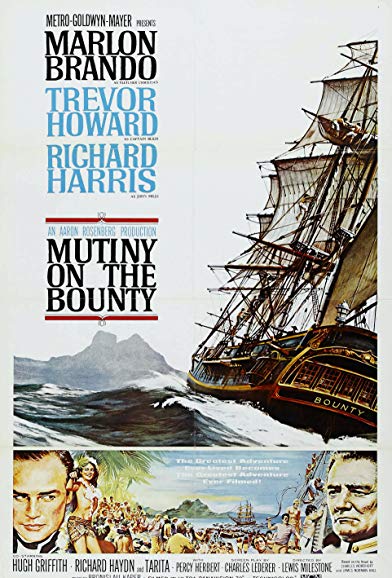

Mutiny on the Bounty, MGM’s lavish Technicolor remake of their classic black-and-white 1935 Best Picture Oscar winner, opened in November to mixed reviews but robust business, mainly on the marquee strength of Marlon Brando, the greatest actor of his generation. Brando played Fletcher Christian, the British naval officer who mutinied in 1789 against the cruelties of Captain William Bligh (Trevor Howard) with the latter carving a place in maritime infamy. Clark Gable and Charles Laughton had immortalized the same roles in the 1935 version, and many critics could not get past their iconic portrayals. But the public didn’t seem to mind the new takes on the historical figures, and made the film the highest grossing movie of December.

The film had been plagued with a prolonged, troubled production with filming commencing in the fall of 1960, and then suffered stops and restarts throughout 1961 and 1962, finally wrapping in August of ’62. after a change of the director’s chair (Lewis Milestone in, Carol Reed out) and constant rewrites of the script. The press gleefully reported all the behind-the-scenes turmoil, focusing on Brando’s self-indulgences, disruptive behavior, and alienation of some of his fellow co-stars, primarily Howard and newcomer Richard Harris. Brando fought back, complaining about the unfinished script and vigorously defended his actions. When the film finally opened, the public flocked to see what all the ruckus had been about. They encountered a skillfully crafted men-against-the-sea epic with South Seas exotica trappings that sailed across the roadshow theater screens in majestic Ultra 70mm. Critics who found favor with the film for the most part looked past the performances, concentrating on the film’s expert production elements (cinematography, score, special effects etc.) and citing the meticulously crafted replica of the original Bounty as the real “star” of the film.

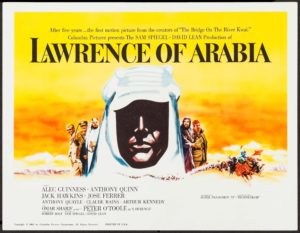

All three films played through the lucrative end-of-the-year holiday season and well into 1963, strategically primed to appeal to Oscar voters viewing them in the roadshow engagements. The movie epics would compete against the last film to open as a roadshow, the highly anticipated Lawrence of Arabia, which arrived in mid-December in New York, followed in select cities by Christmas.

The last of the roadshow epics to open in 1962 turned out to be the best. David Lean’s mammoth production of the WWI Middle Eastern desert campaign focused on T. E. Lawrence, a low level British intelligence officer who rose to heroic heights leading the Arab tribes in revolt against what was left of the the collapsing Turkish empire. Filmed entirely on location overseas, the film is the prime example of international collaboration at the end of the studio era. It also stands as a microcosm of the elements that made 1962 such a pivotal year in film history. The roadshow era would last until the beginning of the 1970s, but the quality of the films presented declined generally as the 60s came to a close. The grandeur of Lawrence of Arabia has notably survived through regular and popular theatrical revival showings, continuing to draw appreciative audiences, who are reminded of what they are missing in contemporary moviegoing.